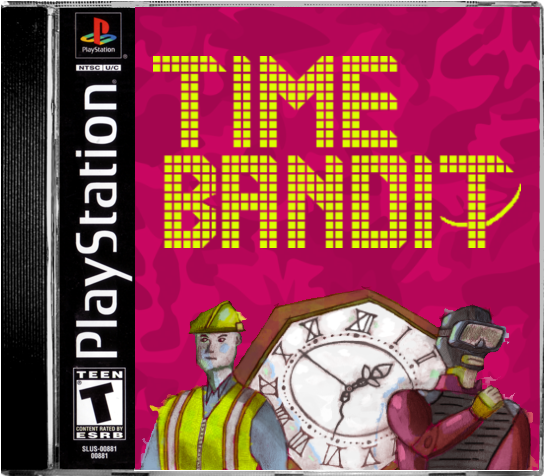

Time Bandit - Stealth Prologue now available!

Yes, Time Bandit is receiving a second prologue chapter!

Why?

Truthfully it’s because the game needs a big marketing push. This is a big, experimental game with a lot of different parts, and for a long time I found it very hard to explain exactly what you *do* in the game or convey how it is, in fact, fun to play. The first prologue was more or less an intro to the story, and that was it. I really like how, in the real-time spirit of things, even the main mechanics are introduced slowly in a tutorial that's spread out over a couple of real-life days. I was happy with it artistically; it begins at the beginning, and I had no problem releasing something like that early on as a teaser to the game. Unfortunately, it was terrible for marketing. These first moments of the game aren't at all representative of the game as a whole. The first prologue has different goals entirely than the game that follows, namely, to introduce a story and set up the idea that this game will give you an unusual experience of time. And certainly, these things can make up part of its appeal. But at the same time, it's leading with the parts that are the most complicated to explain, and it’s just not possible for me to convince people with something like that that there's also a rather traditional game loop to come. And as with most things that stare you right in the face, it took me much longer than you might expect to figure out how to explain exactly what you *do* in the game in the most basic terms. But this is it: Time Bandit is a resource management game in which you try to sneak out time crystals in order to sell them for money, which you need to buy more fuel in order to solve more puzzles to collect more time crystals. See, a loop. It's simple! And it's definitely circular, as a loop should be! And this is a significant part of what people want to hear, I think, when learning about the game, alongside whatever makes it unique (and for that I've developed a line about how this is a "wholesome"-seeming idle adventure game where everything you do takes an unusual amount of time because the company you work for is hiding a dark secret). Around the same time that I finally discovered how to describe Time Bandit, I was also able to do some playtesting, and I quickly realized that I should use a save file to jump people past the whole story intro and into that game loop. Then it wasn't long before I also realized that giving players the opportunity to experience this game loop should have been part of the marketing all along. So, this second prologue does just that: it jumps you ahead to after all the main mechanics are introduced and throws you right into the stealth so you can get a feel for how the game works. I sacrificed some artistic integrity in deciding to release something like this. If you were already sold on Time Bandit and have no need to experience this game loop, I recommend just waiting for the official release so you can experience the real-time mechanics as they’re intended!

A lot of very practical-sounding people say that a game should be made according to what is most marketable and that this is clearly where I should have started. But if you follow this logic to its conclusion – and many do – then you will arrive at the point of thinking that, since this is what sells, it is all that any game should be: an addictive game loop that can be wrapped up all nice and neat under the bow of a marketing hook that fits into a tweet. Don't get me wrong, I think repetition of one sort or another is an important element to just about any one of these things that we call videogames. I'm interested in the expressive power of many of the aesthetic forms that arose in the history of commercial videogames, something that I think is clear enough just from taking a quick glance at Time Bandit. But Time Bandit is certainly more than its game loop as well. It is also, more than anything, the different experiences of time that it’s designed to create. In fact, it’s not just the prologue that’s different from part 1, in which things get into the swing of the game loop: all its parts differ from one another and are designed to create different kinds of temporal experiences, something that will become clearer as the game goes on. I’m interested in expanding and contracting the time frame at which the loop takes place, in breaking it occasionally by offering moments of reprieve and opportunities for reflection. But the game simply offers up these shifts in time as suggestions, intended to craft an experience about the historical forces that shape our temporal experience and how we can challenge them. In the end the player decides how to integrate the game into their life, the habits and rituals that they would like to make with it and, of course, when and whether to play at all.

So all this stuff about time complicates the game loop quite a bit (even if I have found that extending a loop in time, at least, does not make a game less addictive but, in fact, maybe even more so — something that I think is proven by Animal Crossing, but I’m not sure if people believe me when I draw the comparison). They make Time Bandit more difficult to explain and for that reason less straightforwardly marketable. And I would never argue against the basic point of any of those eminently practical capitalists who say you should simply make a more marketable game if you want to sell it to more people. That’s undeniably true. Artists expecting that their ideas, however avant-garde, should turn them into self-sustaining businesspeople are simply bad capitalists, and they’re constantly liable to be led down the path of becoming reactionaries because of it. This is why it can be dangerous to encourage people to get into something so unsustainable, particularly while not being completely forthright about how much capital you’ve invested into marketing and contracted labor yourself. When I began, I was certainly less aware of the need to invest tens of thousands of dollars into marketing, without which quite simply not enough people would hear about the game and it would sink in the algorithms, streamers wouldn’t bother to play it, journalists wouldn’t bother to cover it. It’s not impossible, but then you’re basically counting on having to go viral, and so you’d better have a simple hook and easily GIFable game (Time Bandit has neither). I know this is starting to sound a lot like I’m complaining, but to be clear, I’m not – least of all about my personal problems with marketing a videogame. Indie game development, at least as it exists in the current context, is a privilege, not a social cause to be championed. When you’re marketing an indie game, the norms of the discourse are to always be positive, to encourage others to make games, to show support for all the other indie developers. I’m not trying to be needlessly negative - not least because I’d like to avoid inviting the dogpiling that I’ve seen coming from those who are invested in a thing— but I do think it’s important to be clear-eyed about the context within which indie game production and the discourse around it currently takes place. Because by making financial success sound easy, you are, at best, creating people who might invest a lot of time into something with the idea of success that will never come and, at worst, creating people who go on to become small business owners who exploit others themselves by contracting out labor and marketing when they realize it’s the only way to make it in the present context.

Time Bandit is as close to a “solo developed” game as such things come. I haven’t contracted out anything. But even then, can I be said to have made this game "all on my own"? When people ask, that’s what I usually say, because I think it’s true according to the implied premises of the question. Of course we think: my playtesters didn’t "make" the game, and neither did the code I took from the Internet, the sound effects I got from freesound.org, my tools (Unity, etc.); my computer didn’t "make" it; and yet think about how much labor in fact went into each of these! And it’s hard to imagine any way around it with something as technically complex as a videogame. The production conditions are such that no one individual should ever be taking credit for anything. Yet everything about our markets demand that we do just that, that someone claim overall ownership, because it is through property claims alone that you are recognized as a business and make money. An interesting way around relying on unpaid playtesters, at least, might be to make a game that doesn’t require playtesting. We tend to think that software has to “function” at some baseline level, but the iterative model of software development is only one way of doing things, which just so happens to produce these neatly wrapped gift box commodities. But I wouldn’t necessarily disagree with the idea that maybe we just shouldn’t be making videogames at all except under socialized conditions of production.

And yet, here I am. I find myself not just making but marketing this game, under the given historical conditions. Even dedicating a lot of time to doing it. Why? Ostensibly because I want to make money in order to continue dedicating my time to working on the game. That’s what I’ve often said. Yet when I take a step back and get out of the mindset of doing the marketing – in which it is easier than almost to be believed to get lost, even when one is an anti-capitalist – I can see how it’s almost as if I were on autopilot. As if I were doing it because it was the thing to do. Listen, I didn’t buy it when I saw people making it out like it was easy to come by financial sustainability making games, yet somehow my actions have still said the opposite. As if deep down I still believed otherwise. That’s the power of this stuff. Does this make me a hypocrite, in the same way as I’ve been accused many times of being a hypocrite for trying to sell an anti-capitalist game “for a profit”? Setting aside the fact that the chances of me making a profit are slim indeed, what does a profit even mean when I’m making something because I enjoy it, when there are no wage laborers and I’m simply making it on my own? Profit is defined as earnings minus cost. My quantitative costs are, then, supposedly just the money I had to spend to live while working on it. Yet what is not counted in that equation is my enjoyment, the skills I learned by doing it, the aim towards a future where I can keep doing it - measurements of profit presume a timespan, but what if I blow that timespan up? When it comes to any analysis of purely capitalist production, or of the wider capitalist economy, things should absolutely be measured by their exchange-value, which is a function of the labor-time with which they have been invested. But life is more than what fits along the tiny plane of capitalist life.

In any case, I think the implication of those saying I shouldn’t sell Time Bandit for a profit is that they think I’m suggesting that it is merely profit that’s the problem. A way of thinking that comes from imagining that the world is suffering only because of what we all see on the surface, the individual motivation for greed, rather than the material fact of EXPLOITATION in the production process that underlies it. Here’s the thing: we’re all in the process of something larger than ourselves. Even if indie game production that doesn’t use wage labor isn’t directly capitalist production, it does participate indirectly in the capitalist production that surrounds it from every side, from its reliance on the tools made by others to its marketing and distribution. For the very same reason, this whole thing will, undoubtedly, come across as insincere marketing posturing as a political rant. And so what? How can anything that I say about my project possibly be conceived otherwise than, at least in part, an attempt at marketing? How can any of us be sincerely, purely free of that in a world that shapes our very being into brands? Who I sincerely am is what I have been made to be, and that is, because of these historical conditions, the brand that I am plus everything else that is me. It doesn’t make me or any of us insincere. There is no opting out from this world. There is no mythical unalienated being. Precisely the problem is to reshape the conditions that make us who we don’t want to be.

And I, like anyone, can’t help but wonder, every step of the way, and more and more lately: Is this actually a good use of my limited time on this planet? I enjoy making the game. And I like making something that can have an impact on people. But couldn’t I have a far greater impact, in far less time, making something that wasn’t a videogame? Especially when factoring in the marketing that must to be done in order to possibly reach an audience?

If I must do marketing, I would have liked to make it a valuable part of the experience in itself by playing with the audience’s expectations, in the way that Metal Gear Solid 2 is notorious for having done. To some extent I’ve attempted that in various ways (most particularly, with this "wholesome" parody trailer), but the obvious limitation that I ran up against is that MGS was really within the milieu of hype for technological innovations in realism; a game that is more experimental on the surface and doesn’t have a mass audience lying in wait for it simply doesn’t have the same opportunities to deconstruct that. I’ve also thought about swinging in the opposite direction and trying to talk to you in plain terms. I’d like to lay bare the production process of the game as well as how I market it, and this is an attempt at that, I suppose. I want these themes of demystifying exactly how this game and others are produced and entered into a market to be on clear display in the game. It’s just as well to discuss them here, as it will be a long time still before I get around to developing them in the game — sometimes it’s nice to just write, without all the technical apparatus implied by developing a videogame. I don't know if there's any audience out there for some longform writing like this anymore, just as I don't know if there's any audience out there for Time Bandit — it’s almost imperative for me to have put this into a video instead — but boy would that make the process of getting it out there a lot more labor intensive and less fun for me. This is how I like communicating, and I hope some of you like reading it. Maybe I'm not talking to anyone at all. But even if I'm just talking to myself — yes, this is marketing (perhaps very bad marketing), and yes, there seems to be a deep paradox when it comes to trying to say what you mean while doing anything connected with marketing, but … idk, here I am, this felt worthwhile to spend time on, and it is at least more me than I’ve felt in other mediums.

Get Time Bandit – Story Prologue

Time Bandit – Story Prologue

Prologue #1

| Status | In development |

| Author | phoenixup |

| Genre | Adventure, Puzzle, Simulation |

| Tags | 3D, Idle, Low-poly, Narrative, PSX (PlayStation), Retro, Singleplayer, Story Rich |

| Languages | English |

More posts

- Big update to the Time Bandit prologue chapter!Feb 04, 2022

- Vote for Time Bandit @ PLAY 2021 - The Creative Gaming Festival today!Nov 10, 2021

- Vote for Time Bandit @ A. MAZE / Berlin today!Jul 23, 2021

- a Marxist scuba diverJul 01, 2021

- Prologue chapter of Time Bandit, unique real-time game with an anti-capitalist n...Jul 01, 2021

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.